Bekannt für seine markante Kombination von Pflanzen- und Tierdarstellungen, die die Dringlichkeit ökologischer Themen veranschaulichen, enthüllt der schwedische Street-Art-Künstler Vegan Flava in diesem exklusiven Interview mit Lilli Green die evolutionäre Reise seiner künstlerischen Identität.

Beitragsbild: „Signs on the surface“ – Vegan Flava

Mit einem Engagement für Umweltbewusstsein und soziale Gerechtigkeit geht Vegan Flava über die Grenzen konventioneller Kunstformen hinaus und definiert seinen Stil als eine Form des „visuellen Aktivismus“ und der „direkten Aktionsmalerei“. Dieser eindringliche Einblick in seine Welt des kreativen Ausdrucks offenbart die subtile Macht der Kunst, die Betrachter zu berühren, zu inspirieren und zu transformieren, während sie gleichzeitig einen dringenden Aufruf zum Handeln im Angesicht der gegenwärtigen ökologischen Krise darstellt.

* original English interview version: please scroll down! *

Interview mit Vegan Flava

Du nennst dich „Vegan Flava“ und betrachtest deine Arbeit als „visuellen Aktivismus“. Könntest du die Geschichte hinter deiner gewählten Aktivistenidentität teilen?

Nun, das war ein sich verändernder und sich entwickelnder Prozess, der mehr als 30 Jahre umspannt. In meiner Jugend in den frühen 90er Jahren war ich in der Hardcore-Punk-Musikbewegung involviert, die zu einer bedeutenden Subkultur unter Jugendlichen in den Industriestädten wurde, in denen ich an der schwedischen Westküste aufgewachsen bin. Die Musik beleuchtete viele soziale, Umwelt- und ethische Themen, aber sie machte mich auch darauf aufmerksam, dass all die kreativen Dinge, mit denen ich mich beschäftigte, genutzt werden konnten, um diese Themen zu erforschen und zu reflektieren. Ich stellte 1998 auf eine pflanzliche Ernährung um und begann wie reflexartig, „Vegan“ in meine Graffiti zu schreiben. Einige Jahre später fügte ich meinem Straßenpseudonym das Wort „Flava“ hinzu. Seit der Jahrtausendwende, während meines Studiums am Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, bemerkte ich, dass ich nicht mehr so viel Graffiti malte und mich auch nicht mehr wie ein gewöhnlicher Künstler fühlte. Das war der Zeitpunkt, an dem ich meine Kunst als visuellen Aktivismus und direkte Aktionsmalerei bezeichnete. Seit meiner Jugend habe ich verschiedene künstlerische Wege erkundet, um mich mit sozialen Themen zu befassen.

Rooted above the taiga / Über der Taiga verwurzelt (Polarfuchs) – Mural in Manhattan New York, kuratiert von East Village Walls

Blue desert / Blaue Wüste (Ostsee-Hafenmarder) – Mural in Stockholm Sweden

Queens crossing the North Sea / Königinnen überqueren die Nordsee (Kurzhaar-Hummelkönigin) – Mural in Penge London, kuratiert von London Calling Blog

Auf deiner Website behandelst du kritische Themen wie das Massenaussterben und den Ökozid. Wie funktioniert deine Kunst als Antwort auf diese dringenden Probleme?

Ich glaube, Kunst ist eine Sprache für Emotionen. Sie kann das Bewusstsein schärfen, Diskussionen anregen und verschiedenen Dingen visuelle Präsenz verleihen. Ich hoffe, dass meine Kunst genau das bewirkt, einen Dialog mit dem Betrachter zu initiieren, der Emotionen und Gedanken hervorruft, die zu einer neuen Vision führen können – das geschieht auch bei mir. Ich visualisiere Themen aus meiner lokalen Natur, die sich auf Pflanzen und Tiere an Land und in Seen und der Ostsee beziehen. Ich arbeite mit verschiedenen Kontexten und Methoden, im öffentlichen Raum mit Street Art, Wandgemälden und Land Art sowie mit Studioarbeiten für Ausstellungen. Die vielfältige und dynamische Arbeitsweise finde ich angenehm und lohnend, sie eröffnet aber auch weitere Möglichkeiten.

Deine Kunst zeigt oft eine Verschmelzung von Pflanzen und Tierbildern. Gibt es eine spezifische Bedeutung oder Botschaft, die du durch dieses wiederkehrende Motiv vermitteln möchtest?

Ich habe mir die Bewegung von Pflanzen und Tieren in Schweden angesehen, die auftreten, wenn sich das Klima erwärmt. Mit der Veränderung der Bedingungen müssen sie entweder anpassen oder umziehen, um zu überleben. Dasselbe gilt für Menschen. Ich wurde vor einigen Jahren erstmals darauf aufmerksam, als ich in Abisko im hohen Norden Schwedens war. Aufgrund des wärmeren Klimas wachsen Büsche und Birken höher auf den kahlen Bergen, was die besondere Natur der Tundra verkleinert. Das bedeutet, dass die Pflanzen und Tiere, die sich darauf spezialisiert haben, in der Tundra zu leben, weiter nach Norden ziehen müssen. Aber mir wurde klar, dass die Welt an der nördlichen Grenze Schwedens endet. Dort gibt es wunderschöne Blumen mit schönen Namen und Tiere, die so ziemlich so weit nördlich sind, wie sie in der Welt kommen können. Ich sehe es als einen Abgrund am Ende der Welt. Die Verschmelzung von Pflanzen und Tieren ist ein Ausdruck der Verflechtung von Lebensformen in den Ökosystemen, aber vor allem ein visueller Ausdruck für die Bewegungen, die Pflanzen, Tiere und Menschen machen müssen, um zu überleben.

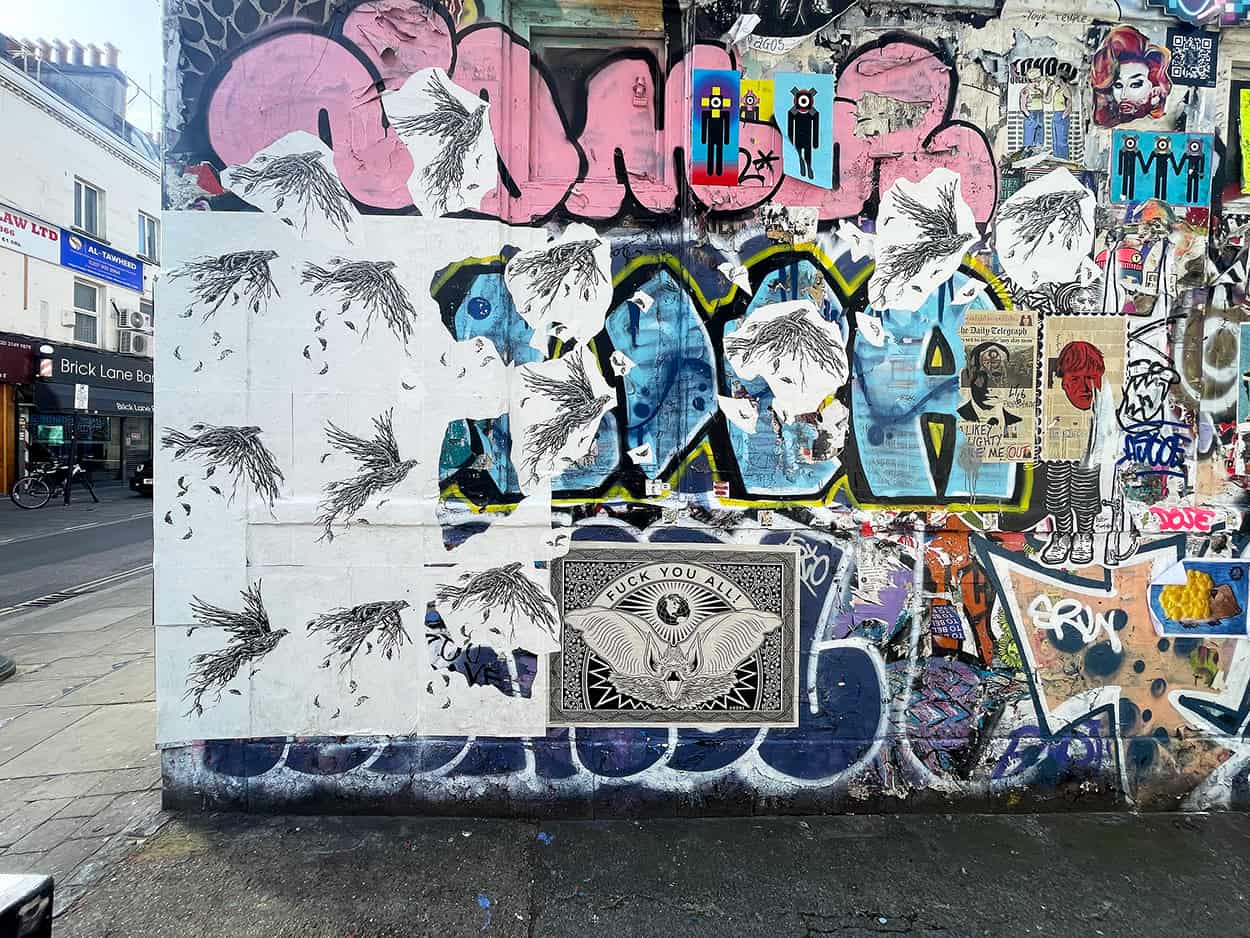

Migration aus dem Anthropozän – Paste-ups in Brooklyn New York und Shoreditch London

Kannst du näher darauf eingehen, wie deine persönliche Verbindung zur Natur deinen kreativen Prozess formt und lenkt?

Ich bin wo ich lebe oft in der Natur, die vielfältig ist und mehrere Seen umfasst. Ich habe es immer geliebt, wenn der Winter mit dem ersten Schneefall kommt. Es sieht aus wie ein riesiges Blatt Papier, das die Landschaft bedeckt. Es hat mich dazu aufgefordert, dort etwas zu erschaffen. Vieles meiner Kunst beginnt mit einem Blatt Papier. Es wird gesagt, dass Papier ein Gedächtnis hat, also muss man vorsichtig sein, wie man damit umgeht. Ich sah, dass der Schnee auch ein Gedächtnis hatte. Jeden Tag gab es mehr Spuren von Aktivität. Ich dachte daran, eine Perspektive von oben zu bekommen, also kaufte ich eine Drohne und fuhr mitten auf den See, wo ich lebe, und machte ein Stück auf dem Eis mit Schnee und biologisch abbaubarer Kreide. Ich gab ihm den Titel „A walk on weak ice“ und es war das erste Stück, das ich in einer Serie namens „Signs on the surface“ (Beitragsbild oben – red.) fertiggestellt habe.

Aus deiner Sicht, wie fängt urbane Kunst effektiv die Aufmerksamkeit von Menschen ein und inspiriert sie, bedeutungsvolle Schritte zur Bewältigung von Umweltproblemen zu unternehmen?

Ich denke, urbane Kunst ist wichtig, weil unsere Kunst dort ist, wo die Menschen sind. Sie ist mit dem Alltagsleben verbunden und ermöglicht daher eine entspannte Begegnung mit Kunst. Heutzutage sind Städte die Quelle vieler Umweltprobleme, da die meisten Dinge in die Städte importiert werden und sehr wenig von dem, was wir brauchen, dort produziert wird. Urbane Kunst ist Teil der Schaffung der Umgebungen, in denen wir leben möchten, und kann Inspiration und Diskussionen über die Stadtplanung zukünftiger Städte, die wir brauchen, hervorrufen. Die Anpassung an das extreme Wetter ist bereits akut. Kunst verändert auch die Künstler, da Kunst oft ein breites Feld der Erforschung ist, in dem man Dinge aus erster Hand entdeckt und lernt. Ich weiß, dass wenn ich ein Wandgemälde beende und gehe, ist es ein Samen, zu dem die örtliche Gemeinschaft den nächsten Wachstumsring hinzufügt.

Gibt es bevorstehende Projekte, Stücke oder Ausstellungen, über die du gerne sprechen und berichten würdest?

Ich arbeite an einem Ausstellungsthema mit dem Titel „Tears of the cryosphere“. Winter und Schnee sind tief in der skandinavischen und finnischen Identität verwurzelt. Heutzutage sind die Winter etwa vier Wochen kürzer als damals, als ich ein Kind war, und ich erlebe, dass die Winter instabiler geworden sind. Die Temperatur wechselt schneller von unter Null auf darüber. Es regnet, wo früher Schnee lag, und der nächtliche Schneefall kann bereits tagsüber schmelzen. Wenn der See, in dem ich lebe, gefriert und ich morgens Schlittschuh laufen kann, könnten meine Schlittschuhe mittags ins Eis sinken und ich muss zurücklaufen. „Cryos“ ist alles Wasser in gefrorener Form, See- und Meereis, Permafrost, Gletscher und Schnee. „Sphere“ bedeutet Kugel. Die Kryosphäre ist das Kühlsystem unseres Planeten. Ich betrachte die Auswirkungen in der Kryosphäre aufgrund des sich erwärmenden Klimas und wie sich das auf die Natur hier in Nordeuropa auswirkt. Ich habe die Arbeiten bereits einmal gezeigt und arbeite weiterhin an dem Thema. Ich hoffe, mehr Möglichkeiten zu erhalten, die Ausstellung zu präsentieren.

Zum Webseite und Shop von Vegan Flava: https://www.veganflava.com

In der Druckwerkstatt – Drucken eines Linolschnitts

Ein klarer Schnitt in der Biosphäre – Installation mit Linolschnitten und Eichenblättern

Interview with Street Artist Vegan Flava

Known for his distinctive combination of plant and animal depictions that illustrate the urgency of ecological issues, the Swedish street artist Vegan Flava reveals in this exclusive interview with Lilli Green the evolutionary journey of his artistic identity.

With a commitment to environmental awareness and social justice, Vegan Flava transcends the boundaries of conventional art forms, defining his style as a form of „visual activism“ and „direct action painting.“ This compelling glimpse into his world of creative expression unveils the subtle power of art to touch, inspire, and transform viewers while simultaneously issuing an urgent call to action in the face of the current ecological crisis.

You go by the name „Vegan Flava,“ and see your work as „visual activism.“ Could you share the story behind your chosen activist identity?

Well, it’s been an changing and evolving process spanning more than 30 years. In my youth in the early 90s I was involved in the hardcore punk music movement which became a significant subculture among youth in the industrial cities where I grew up on the Swedish west coast. The music shed light on many social, environmental and ethical issues, but also made me aware of, all the creative things I was into, could be used to explore and reflect these issues. I turned to a plant based diet in 1998 and like a reflex from that started writing ”Vegan” in my graffiti. Some years later I added the word ”Flava” to my street alias. From the turn of the millennia, during my studies at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, I noticed I didn’t paint much graffiti anymore and I didn’t feel like an ordinary artist either. That’s when I started calling my art visual activism and direct action painting. Ever since my teenage youth I’ve explored different artistic ways of engaging in social issues.

On your website, you address critical topics like mass extinction and ecocide. How does your artwork function as a response to these pressing issues?

I believe art is a language for emotions. It can raise awareness, discussion and give visual presence to different things. I hope my art does that, initiate a dialogue with the viewer that evoke emotions and thoughts which might lead to a new vision, that’s what it does to me as well. I’m visualizing issues from my local nature, related to plants and animals on land and in lakes and the Baltic Sea. I work with several contexts and methods, in public space with street art, murals and landart, and also studio work for exhibitions. The varied and dynamic way of working is something that I find pleasant and rewarding, but also widens the opportunities.

Your artwork often features a fusion of plant life and animal imagery. Is there a specific significance or message you aim to convey through this recurring theme?

I’ve looked at the movement of plants and animals in Sweden that occur when the climate warms. As the conditions for plants and animals change, they either need to adapt or move to survive. The same goes for humans. I was first struck by it several years ago when I were in Abisko in the far north in Sweden. Due to the warming climate the shrubs and birch trees grow higher upp on the bare mountains, making the special nature of the tundra smaller. It means that the plants and animals that have specialized in living in the tundra need to move further north. But I realized that the world ends at the Swedish northern border. There’s beautiful flowers with beautiful names and animals that are about as far north they can get in the world, so I see it as a precipice of the end of the world. The fusion of plants and animals are an expression of the intertwining of lifeforms in the ecosystems, but foremost a visual expression for the movements plants, animals and humans need to make to survive.

Can you expand on how your personal connection with nature shapes and guides your creative process?

I am often out in the nature where I live, which is diverse and has several lakes. I’ve always loved when winter comes with the first snowfall. It looks like a giant sheet of paper covering the landscape. It was calling on me to create something out there. Much of my art starts with a paper. It is said that paper has a memory, so be careful how you treat it. I saw that the snow had a memory too. Every day there was more traces from activity. I was thinking of getting a perspective from above so I bought a drone and skated out to the middle of the lake where I live and did a piece on the ice with snow and biodegradable chalk. I gave it the title A walk on weak ice, and it was the first piece I accomplished in a series I call Signs on the surface.

From your perspective, how does urban art effectively capture the attention of individuals and inspire them to take meaningful steps towards addressing environmental concerns?

I think urban art is important because our art is where people are. It’s intertwined with everyday life and therefore gives rise to a relaxed encounter with art. Today cities are the source to many environmental problems as most things are imported to cities and very little of need are produced in them. Urban art is part of making the environments we want to live in and can inspire and evoke discussion about city planning of the future cities we need. Adaptation to the extreme weather is already acute. Art also change the artists as art is many times a broad field for exploration where you discover and learn things first hand. I know that when I finish a mural and leave, it is a seed to which the local community adds the next growth ring.

Are there any upcoming projects, pieces, or exhibitions on the horizon that you’d like to share and talk about?

I’m working on an exhibition theme ”Tears of the cryosphere”. Winter, and snow is deeply rooted in Scandinavian and Finnish identity. Today the winters are about four weeks shorter than when I was a kid and I’m experiencing that the winters are more unstable. The temperature shifts faster from below zero to above. It’s raining when it used to snow and the nights snowfall can melt already during the day. If the lake freeze where I live, and I can go skating in the morning, my skates might sink into the ice at noon and I need to walk back. ”Cryos” is all water in frozen form, lake and sea ice, permafrost, glaciers and snow. ”Sphere” means globe. The cryosphere is our planets cooling system. I’m looking at the effects in the cryosphere due to the warming climate and how that affects the nature here in northern Europe. I’ve showed the works once and I’m continuing to work on the theme and I hope to get more opportunities to show the exhibition.

Oktober 2023 / Vegan Flava

Das könnte Ihnen auch interessieren:

Rise Up Residency – Street Art für den Meeresschutz

Interview mit dem britischen Streetartist und Tierschützer Louis Masai

Upcycling Kunst aus Portugal als Statement gegen Plastikmüll

Street Artist ROA widmet seine Tiermalereien der Artenvierfalt

Interview mit dem Künstler Vegan Flava – Die Symbiose von Natur, Kunst und Aktivismus